Attachment and Attention-Seeking Behaviour in Young Children: Understanding the Connection

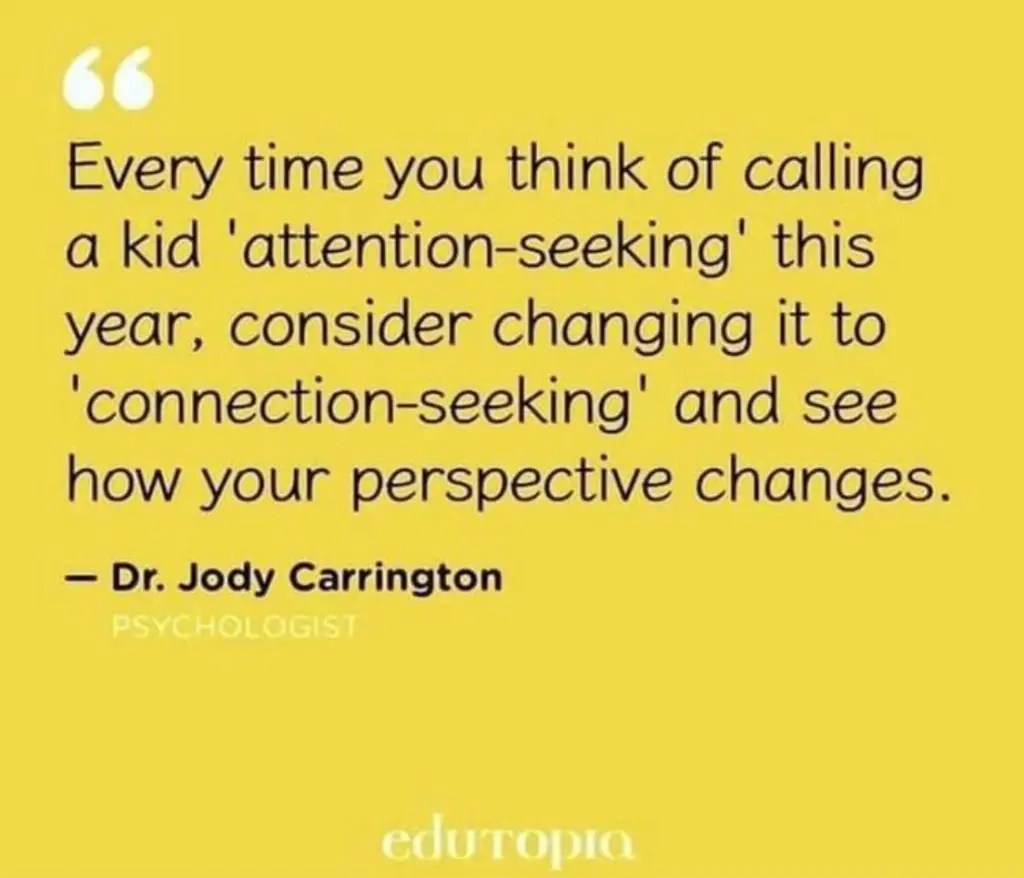

Attention-Seeking Behaviour or Connection Seeking?

When it comes to understanding the social and emotional development of young children, attachment theory has long been a cornerstone of both research and practice. Developed by British psychologist John Bowlby in the mid-20th century, the theory posits that the quality of the early relationships between children and their primary caregivers can have a profound and lasting impact on their later development and wellbeing. To many times I have heard adults say a child is attention-seeking. This is usually a child they are struggling to support. We need to reframe this and as educational professionals and parents look into the behaviour further.

In this article, we delve into the ways in which attachment may influence what is often labelled as attention-seeking behaviour in young children, and explore strategies that educators can use to support healthy development. More and more in our training we are moving away from attention seeking to “Attention Needing” or even bypassing this label completely to be more specific i.e “When adult attention is switched to another”, this might indicate a transition issue. I have also seen this reframed at “Connection Seeking”. This terminology helps make links between behaviour and attachment clear.

The Basics of Attachment Theory

At its core, the theory focuses on the emotional bond that forms between a child and their primary caregiver, typically their mother. According to Bowlby, the nature of this bond can be classified into four distinct attachment styles:

- Secure: The child feels safe and secure, knowing that their caregiver is consistently available and responsive to their needs.

- Anxious-ambivalent attachment: The child is uncertain about the availability of their caregiver and may become clingy or overly dependent.

- Anxious-avoidant: The child learns to suppress their needs for attachment and may become detached or emotionally distant.

- Disorganised attachment: The child displays a mix of behaviours, often as a result of inconsistent or chaotic caregiving.

These attachment styles have been generally accepted to be largely shaped by the caregiver’s responsiveness, sensitivity, and consistency in meeting the child’s needs. Importantly, these early attachment experiences can have a significant impact on a child’s later social, emotional, and cognitive development.

Attachment and Attention-Seeking Behaviour

Attention-seeking behaviour in young children can manifest in various ways, such as tantrums, clinginess, aggression, or constant demands for attention. While some level of attention-seeking is natural and developmentally appropriate, excessive or maladaptive attention-seeking can be a sign of underlying attachment issues.

Children with insecure attachment styles may be more prone to attention-seeking behaviour, as they attempt to elicit caregiving responses from their adult caregivers. For example, a child with an anxious-ambivalent attachment style may become overly clingy or demanding in an effort to ensure that their caregiver remains close and attentive. Similarly, a child with an avoidant attachment style may use attention-seeking behaviours as a way to maintain a sense of control in their relationships.

Supporting Healthy Attachment in the Classroom

As teachers the more we understand about the potential impact of attachment on the behaviour and development of young children the more effective we may be at supporting them. I think we should also state that we should not attempt to take the role of a parent, we don’t spend enough time with the children we support. The strategies below can help make the child feel safe and ready to learn in our classrooms.

Strategies for supporting healthy attachment in the classroom:

- Consistency and predictability: Establishing a consistent daily routine and clear expectations can help to create a sense of security for students, particularly those who may have experienced inconsistent caregiving at home.

- Emotional attunement: Being sensitive to and validating children’s emotions can help to build trust and strengthen the attachment relationship. Encourage open communication and provide a safe space for students to express their feelings.

- Responding to individual needs: Each child is unique, and it is essential to tailor your approach to meet their specific needs. This may involve offering extra support or adaptations for students who display signs of insecure attachment or attention-seeking behaviour.

- Creating a nurturing environment: Foster a positive and inclusive classroom culture where all students feel valued and supported. Encourage cooperation, empathy, and respect among students to promote healthy relationships.

- Collaboration with parents and caregivers: Build strong partnerships with parents and caregivers to support the child’s development both at home and in school. Share information about the child’s progress and work together to address any concerns or challenges.

By creating a secure and supportive classroom environment, we can help to address the underlying attachment issues that may be driving these behaviours and promote healthy social and emotional development for all students.

Critiques of attachment theory:

- Attachment theory focuses too narrowly on the caregiver-infant dyad and does not adequately consider the broader social and cultural context in which development occurs. Attachment is shaped by many factors beyond just caregiver-infant interactions.

- Attachment theory emphasises the importance of a single primary caregiver, usually the mother. But many children develop secure attachments to multiple caregivers or secondary attachment figures. The theory does not fully account for these alternative attachment relationships.

- The theory implies that attachments develop in a straightforward linear manner, but attachment relationships are complex and dynamic. Attachments can fluctuate based on life events, transitions, and relationships. The theory lacks nuance in how it conceptualises attachment stability and change.

- Attachment theory relies too heavily on the strange situation procedure as the sole measure of attachment. But attachment relationships cannot be reduced to behaviours in a single stressful setting. Multiple methods should be used to assess the complexity of attachment relationships.

- Attachment theory focuses primarily on infancy and early childhood but has little to say about attachment beyond age 5. More research is needed to understand attachment in middle childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.

- the use of disorganised attachment in child protection whereby they note that for many, such a designation for a child has become shorthand for child maltreatment.

The Problem With Labelling Behaviour as Attention Seeking

The concept of “attention-seeking behaviour” implies that individuals act in problematic ways solely to gain attention from others. This is a flawed and superficial understanding of human behaviour that ignores the relational context in which behaviour occurs. From a relational perspective, there are several issues with labelling behaviour as simply “attention seeking”. why does a child need to display behaviour to get an adult to pay attention to them?

How To Deal With Attention Seeking Behaviour

There are many strategies you could choose to deal with attention seeking behaviour. First reflect on the following points and decide if the child is actually connection seeking.

- Behaviour is a form of communication. What is termed “attention-seeking behaviour” is often an individual’s attempt to express a need for connection, affection, or security. Rather than dismissing it as manipulative, it is better understood as a call for care that requires a caring, attuned response.

- Behaviour cannot be separated from the relational context. How individuals act depends on their expectations of relationships based on attachment history. Those labelled as “attention seekers” may have learned that the only way to get emotional needs met is through extreme behaviour. They are adapting to a relational context, not acting in a vacuum.

- Labels are often judgments that damage relationships. Terms like “attention seeker” shame and blame individuals in a way that hinders healthy attachment relationships from developing. Compassion and understanding are more constructive responses.

- Every individual’s behaviour makes sense given their experiences. There are always reasons behind behaviour, even if they are not immediately apparent. It is better to take a curious and validating approach rather than making assumptions about intentions or motivations.

- Relationships require effort and compromise. Healthy relationships are built through responding sensitively and consistently to another’s needs and bids for connection. Rather than viewing “attention-seeking behaviour” as problematic, view it as an opportunity to strengthen the relationship through sensitive care and validation.

Labelling behaviour as “attention seeking” is an overly simplistic understanding that ignores the importance of relational contexts and attachment needs in shaping behaviour. With compassion and understanding, seemingly extreme behaviour can often be recognised as a normal effort to get reasonable needs met in a relationship. The solution is to build a caring relationship, not dismiss the communication from the individual.

References

Dagan, Or & Schuengel, Carlo & Verhage, Marije & van IJzendoorn, Marinus & Sagi-Schwartz, Abraham & Madigan, Sheri & Duschinsky, Robbie & Roisman, Glenn & Bernard, Kristin & bakermans-kranenburg, Marian & Bureau, Jean-François & Volling, Brenda & Wong, Maria & Colonnesi, Cristina & Brown, Geoffrey & Eiden, Rina & Fearon, Richard & Oosterman, Mirjam & Aviezer, Ora & Cummings, E. (2022). Configurations of mother‐child and father‐child attachment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems: An individual participant data (IPD) meta‐analysis. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2021. 10.1002/cad.20450. Accessed Online June 2023

Gross, J.T., Stern, J.A., Brett, B.E., & Cassidy, J. (2017). The multifaceted nature of prosocial behavior in children: Links with attachment theory and research. Social Development, 26, 661-678.

Joy, E.A. (2021). Reassessing attachment theory in child welfare. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work.

Profe, W., Wild, L.G., & Tredoux, C.G. (2021). Adolescents’ responses to the distress of others: The influence of multiple attachment figures via empathic concern. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38, 1671 – 1691. Accessed Online June 2023

White, L.O., Schulz, C.C., Schoett, M.J., Kungl, M., Keil, J., Borelli, J.L., & Vrtička, P. (2020). Conceptual Analysis: A Social Neuroscience Approach to Interpersonal Interaction in the Context of Disruption and Disorganization of Attachment (NAMDA). Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11. Accessed Online June 2023

Please note that this post contains affiliate links that help support our hosting costs.