Understanding the Cycle of Challenging Behaviour

Understanding the Cycle of Challenging Behaviour: A Guide for Teachers

As teachers, we often encounter a range of behaviours in our classrooms, some of which can be challenging and disruptive. Understanding the cycle of challenging behaviour is crucial in managing these behaviours effectively and providing supportive learning environments for all students. This understanding can help teachers anticipate and mitigate potential issues, ultimately fostering better student engagement and learning outcomes. This document on supporting students with trauma in the classroom is brilliant.

Defining Challenging Behaviour

Challenging behaviour refers to any behaviour that interferes with a child’s learning, engagement, and social interactions. It can include physical aggression, disruption, non-compliance, withdrawal, or self-injury. Challenging behaviour is often a form of communication or a response to an environment or situation that the child finds hard to cope with.

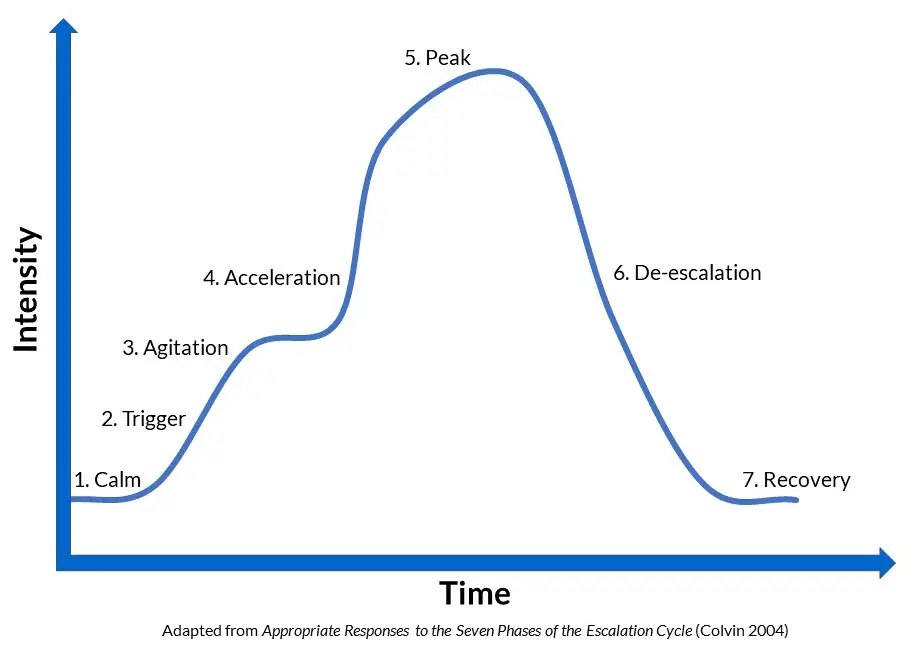

The Cycle of Challenging Behaviour

The cycle of challenging behaviour typically involves four stages: trigger, escalation, crisis, and recovery. This cycle is not static and can vary depending on the individual and the specific context.

Stage 1: Trigger

Every challenging behaviour begins with a trigger, an event or situation that initiates the behaviour. Triggers can be external (e.g., a change in routine, a loud noise, an unstructured situation) or internal (e.g., hunger, tiredness, feeling unwell). They can be obvious and occur immediately before a behaviour incident or Slow Triggers that build up over time and can be harder to recognise. Recognising potential triggers is the first step in preventing challenging behaviours. I have often heard staff say that an incident came “out of the blue” or had no trigger. This may be because of internal antecedents or a slow build up of issues.

Stage 2: Escalation

Following the trigger, the child’s behaviour begins to escalate. This may start as mild signs of agitation or discomfort and gradually increase in intensity. The escalation phase might involve behaviours like fidgeting, becoming argumentative, clenching fists, raising voice, or displaying defiance.

Stage 3: Crisis

The crisis stage is the peak of challenging behaviour. It’s when the behaviour becomes most severe and potentially harmful. The crisis might involve shouting, crying, aggression, complete withdrawal, or other extreme behaviours. This stage is the most difficult to manage and requires clear crisis intervention strategies to ensure the safety of the child and others.

Stage 4: Recovery

After the crisis, the child enters the recovery phase, characterised by a decrease in challenging behaviour. The child might become quiet, withdrawn, or may express remorse or confusion about what just happened. It’s important to provide support during this stage, allowing the child to calm down and regain control.

Responding to the Stages of the Cycle of Challenging Behaviour

Understanding the cycle of challenging behaviour can help teachers develop effective strategies to prevent and manage these behaviours.

1. Identify and Manage Triggers

By observing and understanding a child’s triggers, teachers can often prevent challenging behaviour. This might involve adjusting the learning environment, providing additional support during transitions or unstructured times, or ensuring the child’s physical needs are met.

Understanding and managing triggering behaviours in children is a critical aspect of classroom management. More recently, the benefits of a trauma-informed approach in responding to these behaviours are gaining recognition. This article explores this approach and provides strategies for managing behavioural triggers in children, particularly those who have experienced trauma.

Understanding Behavioural Triggers

Behavioural triggers are events, situations, or environmental factors that cause a child to exhibit challenging behaviour. These triggers can be varied and individual to each child. They might include changes in routine, sensory overload, academic pressure, or social conflicts. For children who have experienced trauma, triggers might also include reminders of their traumatic experiences, which can provoke intense emotional reactions.

Trauma-Informed Approach to Behaviour Management

A trauma-informed approach to behaviour management recognises that challenging behaviours often stem from traumatic experiences and unresolved trauma responses. This approach is underpinned by four key principles:

Managing Behavioural Triggers with a Trauma-Informed Approach

- Identify Triggers

The first step in managing behavioural triggers is to identify them. Observing the child closely and understanding their behavioural patterns can help pinpoint potential triggers. Remember, for children with trauma, seemingly inconsequential events could be triggers, reminding them of their past traumatic experiences. - Create a Safe and Predictable Environment

Children, particularly those who have experienced trauma, thrive in environments that are safe and predictable. Regular routines, clear rules, and consistent consequences help create a sense of security. A calming corner in the classroom where children can self-regulate when they feel overwhelmed can also be beneficial. - Build Strong Relationships

Strong, trusting relationships can serve as a protective factor for children with trauma. Show genuine interest in their lives, be consistent and reliable, and express care and empathy. This connection can help children feel understood and supported, reducing the power of triggers. - Teach and Model Coping Strategies

Children who have experienced trauma may need explicit instruction in coping strategies. This could include deep-breathing exercises, mindfulness activities, or using positive self-talk. Model these strategies and provide plenty of opportunities for practice in a safe, low-stress environment. - Collaborate with Professionals

If a child’s behaviour continues to be a concern, collaboration with school counsellors, psychologists, or outside therapists may be necessary. These professionals can provide further insights into the child’s experiences and offer additional strategies for support.

Behavioural triggers in children, especially those rooted in trauma, can be challenging to manage in a classroom setting. However, adopting a trauma-informed approach—understanding the origins of these behaviours, creating a safe environment, building strong relationships, teaching coping strategies, and collaborating with professionals—can significantly improve outcomes. This approach not only helps manage behavioural triggers but also supports the child’s overall well-being and academic success. Ultimately, a trauma-informed approach underscores the critical role teachers play in supporting children’s journey towards healing and growth.

Teaching Students About Emotional Triggers

An important part of building resilience is helping students identify their emotional triggers. What situations make them feel frustrated, stressed, or sad? Our brains create strong associations between past hurtful or traumatic experiences and current events that may resemble them. This can trigger a fight or flight response.

While triggers can help explain emotional reactions, they don’t excuse all behavior. Students still need to develop self-control. That’s where mindfulness techniques come in – recognising overwhelming emotions and asking for help when needed.

Some ways to teach students about triggers:

- Have students list times they felt negative emotions like anger or sadness. Discuss possible triggers.

- Help students create “If…Then…” plans to manage emotional reactions. “If I feel frustrated with my maths work, then I can take three deep breaths.”

- Provide a safe space in class for coping with triggers in healthy ways.

- Distinguish between explanations and excuses. Triggers explain feelings but don’t justify physical behavioural responses

- Teach mindfulness strategies students can use when emotions become overwhelming, and how to seek help.

- Seek specialist support for students struggling with chronic emotional triggers.

The goal is to build awareness of personal triggers and equip students with skills to handle them. With care and compassion, teachers can guide students through understanding and managing their emotional responses this can reduce the length of the challenging behaviour cycle .

What is a Slow Trigger?

A “slow trigger” refers to a situation that gradually builds up and leads to challenging behavior over an extended period of time, as opposed to a quick, immediate trigger. Some examples of slow triggers include:

- Fatigue – The student becomes increasingly irritable, inattentive or defiant as the day goes on due to lack of sleep or becoming overly tired.

- Hunger – The student’s behavior worsens progressively before lunch or snack times as they become hungrier.

- Transitions – The student struggles more with each transition throughout the day as anxiety or frustration mounts.

- Social stress – Ongoing negative peer interactions or too much social stimulation during the day leads to eventual meltdowns.

- Sensory overload – Exposure to loud noises, crowds, scratchy fabric, etc. over time overwhelms the student’s senses and causes acting out.

- Skill deficit – Continued academic demands in an area of weakness like reading lead to the student shutting down.

- Lack of movement – After long periods of sitting still, the student starts fidgeting, talking out of turn, eloping from seat.

- Lack of communication – The student engages in aggression or self-injury after failed attempts to express needs.

- Lack of predictability – Unclear schedules or frequent activity changes build stress and noncompliance.

Noticing slow trigger situations and intervening early can prevent full-blown behaviour incidents. This may involve schedule adjustments, sensory breaks, praise, preferred activities, or pre-teaching expectations.

2. Recognise and Respond to Escalation: A Trauma-Informed Approach

Early intervention can prevent the behaviour from reaching the crisis stage. If a teacher notices escalation, they might use de-escalation strategies like providing a calm, reassuring presence, offering a preferred activity, or using distraction or redirection. Understanding and managing escalation is a vital aspect of supporting challenging behavior using a trauma-informed approach. Escalation refers to the progressive intensification of a student’s emotional state and behavior, often leading to a crisis if not properly addressed. By recognizing the signs of escalation and responding effectively, teachers can prevent these situations from spiraling out of control.

Recognising Escalation

Recognising escalation is the first step towards intervention. It involves being attuned to changes in a student’s emotional state, behavior, and body language. Here are some common signs of escalation:

- Increase in restlessness or fidgeting

- Sudden withdrawal or disengagement from activities

- Increase in argumentative or defiant behavior

- Physical signs such as clenched fists, tensed muscles, rapid breathing, or flushed face

- Verbal indications like raised voice, abrupt speech, or repetitive questioning

It’s important to remember that each child may display unique signs of escalation based on their personal experiences and coping mechanisms. Therefore, getting to know your students and understanding their individual triggers and responses is crucial.

Responding to Escalation

Once you’ve identified signs of escalation, the next step is to respond effectively. The goal here is to de-escalate the situation and prevent it from reaching a crisis point. Here are some trauma-informed strategies:

- Maintain a Calm, Reassuring Presence: Your demeanor can greatly influence a student’s emotional state. Stay calm and composed, maintaining a soft voice and relaxed body posture. This can help signal to the student that they are in a safe and controlled environment.

- Offer a Preferred Activity: If you notice a student starting to escalate, offering an activity they enjoy can help distract them from their emotional distress. This could be a favorite book, a drawing task, or a quick game. The aim is to shift their focus away from the triggering situation.

- Use Distraction or Redirection: Similar to offering a preferred activity, distraction or redirection involves steering the student’s attention away from the source of distress. This could be as simple as changing the subject, introducing a new task, or encouraging the student to engage in a calming activity like deep breathing or guided imagery.

- Validate and Label Emotions: It’s important to acknowledge the student’s feelings. Validation can make them feel heard and understood, which can soothe their distress. Try to label the emotion you think they’re experiencing (e.g., “I can see that you’re feeling really frustrated right now”), and reassure them that it’s okay to feel this way.

- Provide Space and Time: Sometimes, the best approach is to give the student some space and time to calm down. Ensure they are in a safe space where they can’t harm themselves or others, and let them know you’re there for them when they’re ready to talk or rejoin the activity.

Remember, the effectiveness of these strategies will depend on the individual student, the relationship you’ve built with them, and the specific situation. By using a trauma-informed approach, you can help students manage their emotions effectively and create a safer, more supportive learning environment.

3. Manage Crisis Safely: Ensuring Safety and De-escalation

During a crisis phase in the cycle of challenging behaviour, the main priority is to ensure the safety of the child exhibiting the behaviour, the other students, and yourself as the educator. Managing crises effectively often involves a combination of crisis intervention strategies, providing safe spaces, and implementing effective de-escalation techniques.

Pre-Planned Crisis Intervention Strategies

Having pre-planned crisis intervention strategies is crucial – It saves relying on having to make decisions under stress, you and your team know how to react and respond. These plans should be individualised, taking into account the specific triggers, behaviours, and needs of each child. Usually, these plans should be developed in collaboration with a team, including teachers, SEN teaching assistants and parents. They may be known as Wellbeing Plans, Behaviour Support Plans (BSP) or Behaviour Intervention Plans (BIPs).

The intervention strategies should be clear, concise and easy to follow, the simpler the better, detailing the steps to be taken during a crisis. They should include methods to reduce stimuli, techniques to provide reassurance and calm the child, and guidance on when to seek additional support.

Providing a Safe Space

During a crisis, it can be beneficial to provide a safe space for the child to calm down. This could be a designated area in the classroom—often referred to as a “calm down corner”— equipped with soothing items like stress balls, soft pillows, or books. This space should be a non-threatening, low-stimuli area where the student can retreat to self-regulate and regain control. Our article on creating low-arousal environments goes into this in more depth.

Alternatively, the safe space could be another environment where the child feels secure, such as a wellbeing or outdoor sensory garden. The key is that the location is predictable, accessible, and provides an opportunity for the child to de-escalate away from peers’ view, preserving their dignity. Having an audience during incidents is incredibly unhelpful.

De-escalation Techniques

Effective de-escalation is a critical skill when managing a crisis. We have written a full article about de-escalation techniques. Here are some strategies that can help:

- Maintain Calm: As an adult, your reaction can significantly influence the situation. Maintain your calm, speak in a soft and slow tone, and avoid any sudden movements.

- Use Non-Threatening Body Language: Be mindful of your body language. Ensure it’s non-threatening and respectful. For example, maintain an open posture, avoid direct eye contact, and respect the child’s personal space.

- Validate Feelings: Validate the child’s feelings without necessarily agreeing with their behaviour. Statements like “I can see that you’re really upset right now” can make the child feel understood and heard.

- Offer Choices: When possible, offer choices to the child. This can give them a sense of control over the situation and can aid in de-escalation.

- Use Distraction Techniques: Depending on the child, distraction can be a useful technique. This could involve discussing a favourite topic of the child, suggesting a preferred activity, or engaging in a calming activity.

- Seeking Help: If the crisis does not de-escalate, or if at any point the child’s behaviour poses a risk to their safety or the safety of others, it’s important to seek help from a trained professional, such as a school counsellor or psychologist.

4. The Cycle of Challenging Behaviour: Post-Incident Recovery

The aftermath of a crisis can be a crucial time to support a child’s recovery and growth. It’s an opportunity to understand the situation, learn from it, and build strategies to prevent similar incidents in the future. Here are some trauma-informed strategies to support recovery in children exhibiting challenging behaviour. We discuss this more in depth in our post about debriefing. This includes discussions with the adults.

Comfort and Reassurance

Post-crisis comfort involves helping children regain their sense of safety and stability. Reassure the child that they’re safe and that you’re there to support them. This might involve a calming activity that the child enjoys, such as reading a favorite book or engaging in a preferred art activity.

The goal here is to help the child transition from a heightened state of distress to a calmer, more centered state. It’s not the time for punitive measures or reprimands, but for empathy and understanding.

Discussion and Reflection

Once the child has calmed down, it’s essential to talk about what happened. This conversation should be non-judgmental and empathetic, focused on understanding the child’s experience rather than blaming or shaming them.

Discuss the incident and help them understand their emotions and behavior. For instance, you might say, “You seemed very angry when you couldn’t finish the puzzle. Is that what happened?” This can help the child develop emotional awareness and learn to express their feelings more appropriately.

Teach Coping Strategies

Use this as an opportunity to teach the child coping strategies for managing their emotions. You might introduce them to deep breathing exercises, mindfulness activities, or progressive muscle relaxation techniques. The goal is to equip the child with tools they can use to self-regulate when they start to feel overwhelmed or upset.

Problem-Solving Skills

Finally, help the child develop problem-solving skills to prevent similar incidents in the future. This could involve identifying triggers, discussing alternative responses, and role-playing scenarios.

For example, if the child became upset because they couldn’t complete a task, discuss how they might handle it differently next time. You might suggest, “Next time you’re feeling frustrated with a task, you could ask for help, or take a break and try again later.”

By supporting post-incident recovery in a thoughtful and constructive way, educators can help children learn from their experiences and develop better strategies for managing their emotions and behaviour. This not only supports the child’s mental health and well-being but also contributes to a more positive and supportive learning environment.

Concluding Thoughts on The Cycle of Challenging Behaviour

The cycle of challenging behaviour can be daunting, but understanding it provides teachers with a framework to respond effectively. It’s important to remember that challenging behaviour is often a sign of unmet needs or difficulty in handling emotions or situations. As educators, our role is not only to manage these behaviours but also to teach and support students in developing better coping strategies and social-emotional skills.

References & Further Reading Linked to The Cycle of Behaviour

Hallett, N. (2018). Preventing and managing challenging behaviour. Nursing Standard, 32(26), 51-63.

Hallett, N., & Dickens, G. L. (2017). De-escalation of aggressive behaviour in healthcare settings: concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 75, 10-20.

James, I. A., Reichelt, K., Moniz-Cook, E., & Lee, K. (2020). Challenging behaviour in dementia care: a novel framework for translating knowledge to practice. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 13, e43.

One Comment