Internal Antecedents: Behaviour “Out of the Blue”

Internal Antecedents: Does Behaviour Really Come “Out of the Blue?”

Often overlooked, internal antecedents are an important element in behaviour support. This article is based on my experiences working with Autistic children who also communicate in ways we find challenging. We do our best to find patterns, clues and reasons for episodes of challenging behaviour. When a behaviour if displayed with no noticeable trigger there are a number of reasons that may be behind this. With our students who do not communicate verbally, it is often a case of us forming a hypothesis as to the reason whilst we collect further information about a range of factors that affect that student. I am going to outline three possible drivers that may lead to a behaviour being displayed with no clear trigger.

Looking beyond “No apparent reason”.

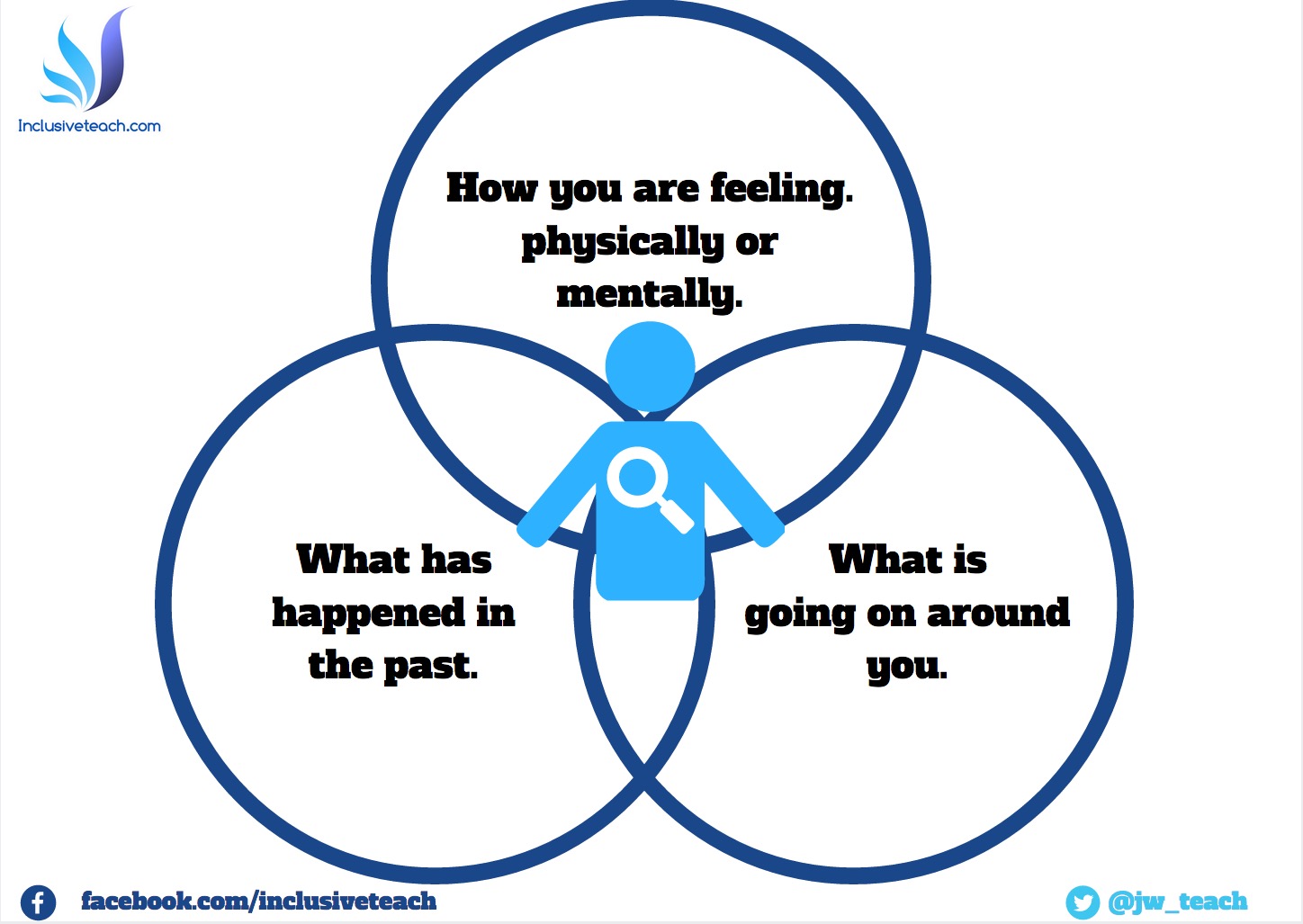

Often challenging behaviour may be due to a mix of setting events and immediate triggers. They may also stem from a combination of internal and external antecedents. The behaviours displayed by our students, both positive and those that are challenging will often be triggered by the interactions between:

- How they feel at that moment.

- What has happened before?

- What is happening around them at that time?

A number of free documents for recording and tracking behaviours are found here.

Setting events

We could think of these as “slow triggers”. They are underlying causes of anxiety or stress that precede the incident occurring. In PROACT training we call these “setting events”. These may precede the incident by a considerable length of time. In some cases this can be many years and be linked to dates of traumatic events, the death of a parent etc or even the expectation of repeated positive events e.g. “last year we visited Disneyland on this date, why not this year?”. Changes in routine can also be setting events. If the routine is “work, snack, garden” then this changes to “work, snack, wait, garden.” The wait may be the setting event of an incident that occurs in the garden. With our students, these changes may be very subtle.

Associative Memory

Many of our students will have a very strong factual memory that allows them to associate an exact memory of the sensations of an experience with current sensory stimuli. The emotional reaction to these events may be positive or may cause the child distress. This means a trigger to an action of concern may not be discernible to the member of staff supporting. This emotional reaction to sensations can lead to self-regulation difficulties for our students as they do not have the language skills available to rationalise their responses [1]. They cannot filter the possible “threat” as a neurotypical student might; triggering a fight, flight, or freeze response. This linked with emotional trauma (as outlined below) can lead to an immediate panic response when common stimuli occur again. This can be a smell, sight, sound, colour, item of clothing, environment, situation or date. These can even be what is called slow-triggers.

What is a Slow Trigger?

A slow trigger linked to challenging behaviour refers to a situation where there is a delayed or prolonged response to a stimulus. Some key things to know about slow-trigger behaviour antecedents:

- The trigger is some kind of event or stimulus that could provoke an immediate response, but for whatever reason doesn’t. With a slow trigger behaviour, the response is delayed – the behaviour will manifest later on.

- Common examples include slow anger responses where frustration builds up over time rather than emerging immediately.

- It could be that the child didn’t get enough sleep, this has the effect of lowering tolerance so usual routines become harder and the capacity to mask is reduced.

- The delay or prolonging of the response is what distinguishes it from a typical quick-trigger reaction. The individual or animal appears unresponsive at first.

- Underlying causes can include high pain tolerance levels, internal processing of emotions, or physiological factors that slow neural or hormonal reactions.

- In some cases, it represents an inability to respond quickly that could become problematic, like slow reflexes. But in other contexts it may be adaptive, allowing more thoughtful reaction.

- Triggers that normally cause a fight or flight response will instead provoke a delayed, drawn-out response pattern rather than an instantaneous reaction.

Examples of Slow Triggers

Here are some examples of slow triggers that can contribute to problem behaviors over time:

- Lack of sleep – Sleep deprivation lowers frustration tolerance and self-regulation.

- Hunger – Going too long without eating leads to irritability, difficulty concentrating, and emotional outbursts.

- Thirst – Dehydration can cause headaches, fatigue and mood issues.

- Sensory overload – Too much noise, light, crowds can create sensory overload, leading to meltdowns.

- Poor nutrition – Diets high in sugar and low in protein/nutrients negatively impact focus and behavior.

- Lack of exercise – Insufficient physical activity increases restlessness and distractibility.

- Academic frustration – Ongoing difficulty with schoolwork lowers self-esteem and motivation.

- Bullying – Repeated teasing or exclusion wears down resiliency and coping skills.

- Chaotic home/classroom life – Constant yelling, stress, or lack of routine/structure is emotionally taxing.

- Excess screen time – Too much technology can interfere with sleep, human interaction and attention.

- Undiagnosed learning issues – Unidentified problems like ADHD or dyslexia lead to acting out.

- Temperature – Especially extended periods of hot weather.

- Lack of social support – Isolation and loneliness due to exclusion or rejection contributes to depression.

Paying attention to slow-moving variables that degrade a child’s baseline functioning allows for early intervention before behaviors escalate. Tracking trends over time helps identify the underlying need a behavior fills so it can be addressed appropriately.

Emotional Trauma

Many of the students we work with have undergone emotional trauma of some sort, whether it be sustained exposure to aversive stimuli, negative experience of school, physical assault or even witnessing traumatic events. Post-traumatic stress occurs when there is a severe negative influence on the nervous system. This can be one incident or long-term exposure to distressing sensory stimuli. Many of our students are unable to control their immediate environment and this can lead to them being unable to feel safe. This constant feeling of panic can have long-term impact on the nervous system.[2] This, in turn, may lead to the child being emotionally reactive and defensive to seemingly non-aversive situations. In training, we talk about being the child’s emotional brakes. We can control our reactions and must be compassionate to the challenges our students face.

Internal Antecedents

The prevalence of triggers to challenging behaviour will vary according to each individual.

Although it is worth acknowledging that the senses we primarily use – sight and hearing will differ from our students whose perception of the environment differs. For example, smells and touch may be more important to a student than auditory input.

What is This Behaviour Telling Us?

It is only through the student expressing discomfort in some way or our interpretation of changes to their presentation that we will be able to gain a clue as to the cause. The better we know the student the more effective we will be on picking up these changes. We can also use a student’s historical behaviour data and medical history to determine the likelihood of internal antecedents existing. For example, if they have a history of hayfever or constipation then we can begin to identify possible issues they are facing. As headaches and other pain are so difficult to identify think medical is a good first thought. If we know they have trouble processing temperature changes and regulating these we need to think about ways to mitigate the impact of these natural variations in the environment.

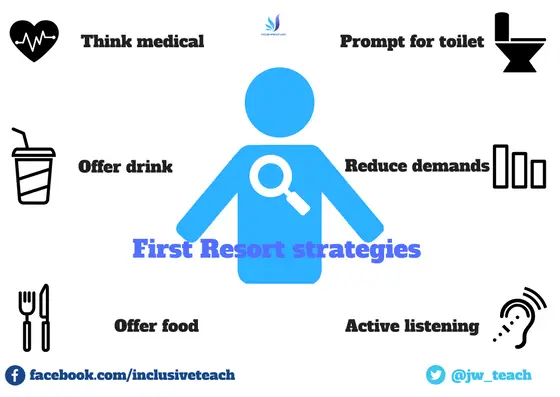

First Resort Strategies

The more we know about the student and what has happened earlier the better picture we can build as to their current situation. This is where communication books are useful. If we know the student ate well at breakfast then hunger is unlikely to be the cause, if they woke up really early or went to bed late then tiredness is a likely cause and we can adapt our approach accordingly.

Internal Antecedent: Self-Esteem & Control

Another type of internal antecedent may be within the student’s cognitive or mental environment,[3] their thoughts, self-esteem, fears and desires. Many of our students have rigid internal rules that are often a way of them controlling the environment and creating reliability and consistency in their lives. Examples I have come across are “you shouldn’t wear glasses”, “The windows should always be closed”. “That box goes on that shelf”. In these situations, social stories and visual explanations may be useful. The following is a very simple list of strategies to work through if you are unsure.

- Think medical!

- Active listening

- Lower demands

- Offer a drink

- Offer Food (Low blood sugar)

- Prompt for toilet

- Social story or explain minor changes.

References & Further Reading About Internal Antecedents:

[1] Connor,M et al (2017) Anxiety in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Evidence-Based Assessment and Treatment

[2] Nason, B (2014). The Autism Discussion Page on the core challenges of autism: A toolbox for helping children with autism feel safe, accepted, and competent (accessed online)

[3] Institute for Applied Behaviour Analysis, Newsletter Volume III, 1997 (Accessed online)

One Comment