What is Inclusive Education? A Guide for UK Teachers

Definition of inclusive education

We have discussed Inclusive education many times on inclusiveteach.com. Currently I am taking part in the Inclusion Leadership project for Kent County Council so have been reflecting on this more and more. Each school needs to determine what inclusion means to them, this shared vision for inclusion should be based on the following principles. To be effective the definition cannot be abstract, it needs to be fully understood by all staff in the school. Inclusive education is an approach to teaching and learning that aims to provide equal opportunities for all students, regardless of their individual abilities, backgrounds, or needs.

This educational philosophy seeks to create a supportive and accessible learning environment where students with and without disabilities can learn alongside each other, fostering a sense of belonging, mutual respect, and appreciation for diversity. Inclusive education emphasises the importance of adapting teaching methods, curricula, and resources to cater to the unique strengths and challenges of each student, ensuring that every learner can reach their full potential and participate fully in the educational experience. Throughout this article I use the term teachers but that includes all school staff. A school is only inclusive if it functions as a community.

Inclusion in the UK Education System

Inclusion in education in the UK has been a hotly debated political topic for many years. There are many different opinions on what inclusion means and how it should be achieved. Some people believe that inclusion means that all children should be educated in the same schools, regardless of their disabilities or learning difficulties. Others believe that inclusion means that children with disabilities or learning difficulties should be educated in separate schools or classes.

There are pros and cons to both of these approaches. One of the benefits of inclusive education is that it can help to break down stereotypes and prejudices about people with disabilities. It can also help to create a more diverse and inclusive society. However, inclusive education can also be challenging. It can be difficult to provide the necessary support for children with disabilities in mainstream schools. It can also be difficult for teachers to meet the needs of all of their students. There are beacons of inclusive practice in schools across the country and I have been lucky enough to visit some in Kent.

The UK government has made a commitment to inclusive education. The 2010 Equality Act requires schools to make reasonable adjustments to ensure that all children are able to participate in education. However, there is still a lot of work to be done to make inclusive education a reality in the UK. I have always worked in Special Schools and it is through this lens that I approach the topic. I do struggle to see how at the current time full inclusion would work.

Importance and purpose of inclusive education in the UK context

The importance of inclusive education in the UK context stems from several factors that highlight the need for an equitable and diverse educational system. These factors include:

- Legal requirements: The UK has enacted laws and policies, such as the Equality Act 2010 and the SEND Code of Practice (2015), which mandate the provision of equal opportunities for all learners, regardless of their abilities, backgrounds, or needs. Inclusive education is essential for schools to comply with these laws and uphold the rights of students with disabilities.

- Demographic diversity: The UK has a diverse population with varied cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic backgrounds. An inclusive education system ensures that all students, irrespective of their differences, have equal access to high-quality education and can benefit from a learning environment that embraces and celebrates diversity.

- Social cohesion: Inclusive education promotes social cohesion by fostering understanding, empathy, and respect among students from different backgrounds and abilities. This helps to reduce prejudices, stereotypes, and discrimination, ultimately contributing to a more harmonious and inclusive society.

- Addressing the attainment gap: Research has shown that students with disabilities and those from disadvantaged backgrounds often face an attainment gap compared to their peers. Inclusive education aims to close this gap by providing tailored support and resources that meet the diverse needs of all learners, ensuring that every student has the opportunity to succeed academically.

- Maximising potential: Inclusive education recognises that each student has unique strengths and talents, and it seeks to nurture these by providing an accessible and supportive learning environment. This approach helps to maximise the potential of all learners, which is beneficial not only for the students themselves but also for society as a whole.

- Preparing students for the future: In today’s globalised and interconnected world, it is essential for students to develop the skills and attitudes required to collaborate and thrive in diverse workplaces and communities. Inclusive education plays a crucial role in fostering these skills and equipping students for a successful future.

Key Principles of Inclusive Education for UK Teachers

Inclusive education is a vital aspect of a modern, equitable educational system. As a teacher in the UK, understanding and implementing the key principles of inclusive education is essential to support all students in reaching their full potential. This article will explore the key principles of inclusive education, drawing on research, insights from academics and published guidance to provide a comprehensive understanding for teachers. Where possible I have used free access articles – all the links are in the references at the end.

Diversity and Individual Differences as Strengths

Inclusive education recognises that every student is unique, with their abilities, needs, and backgrounds. This approach embraces diversity and sees individual differences as strengths, rather than challenges (Ainscow, 2016). By valuing diversity, teachers can create a learning environment that fosters mutual respect, understanding, and empathy among students, promoting social cohesion and reducing prejudice (Ainscow, Booth, & Dyson, 2006).

Equal Opportunities for All Learners

Inclusive education aims to provide equal opportunities for all students, regardless of their abilities, backgrounds, or needs (Norwich, 2014). This means ensuring that every student has access to high-quality education, tailored support, and the necessary resources to succeed academically. By removing barriers to learning and providing appropriate accommodations, teachers can create an inclusive environment that allows all students to thrive (Florian, 2014).

A Focus on Social, Emotional, and Academic Growth

Inclusive education recognises the importance of fostering social, emotional, and academic growth for all students (Rix, Sheehy, & Fletcher-Campbell, 2014). By implementing social and emotional learning (SEL) strategies alongside academic instruction, teachers can support the development of key skills such as self-awareness, self-regulation, empathy, and collaboration (Humphrey, 2013). These skills are essential for students to succeed in school and beyond, promoting well-being and resilience in the face of challenges (Humphrey & Wigelsworth, 2016).

Collaboration between Students, Teachers, Families, and Communities

Creating an inclusive educational environment requires collaboration between students, teachers, families, and communities (Ekins & Grimes, 2009). By involving all stakeholders in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of inclusive education practices, teachers can ensure that their approaches are responsive to the diverse needs of their students (Ekins, 2015). This collaborative approach also fosters a sense of shared responsibility for the success of all learners, promoting a culture of inclusion both within and beyond the school setting (Ekins, 2015). I have written about the impact of the community on wellbeing but I think it app;ies equally to inclusivity.

Tailoring Teaching Methods for Inclusion

Inclusive education requires teachers to be flexible and adaptable in their teaching methods, responding to the unique strengths, challenges, and learning preferences of each student (Black-Hawkins, 2010). This can be achieved through strategies such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and differentiated instruction, which focus on providing multiple means of representation, engagement, and expression to cater to diverse learners (Rose & Meyer, 2002; Tomlinson, 2014). By tailoring their teaching methods, teachers can support the academic success and personal growth of all students, regardless of their individual needs (Hart, Dixon, Drummond, & McIntyre, 2004).

Professional Development and Support for teachers

To effectively implement inclusive education, teachers require ongoing professional development and support (Loreman, 2010). This includes training in evidence-based strategies for inclusive teaching, as well as opportunities for reflection and collaboration with colleagues (Forlin, 2010). The pressure on time for professional development will always be a challenge, lots of courses are available for school staff on different conditions but it essential these can be applied in the school context.

Assessing the Impact of Inclusive Practice

Successful inclusive education requires more than just getting students with disabilities into mainstream classrooms. It requires transforming school systems and cultures to be truly inclusive and meet the needs of all students. Key elements of successful inclusive education include: clear definitions and targets, implementation strategies, teacher training and support, inclusive school leadership, and enabling national policies.

Measuring inclusive education impact goes beyond student access – it also includes evaluating education quality, outcomes and student experiences. Understanding teacher practices is also important. Tools like the Index for Inclusion and Supporting Effective Teaching project help assess inclusive education.

Successful implementation at school level requires: school reviews and plans, training all teachers in inclusive practices, and supporting school leaders with an inclusive vision. At national level it requires: enabling policies, data management systems, curriculum flexibility, and coordination with post-school systems like employment.

School Reviews

It can be difficult to assess if you truly are an inclusive setting. School reviews are a key part of implementing successful inclusive education, according to the Implementing Inclusive Education (2018) report. They allow schools to evaluate their current situation and identify areas for improvement. Some key points about school reviews:

• They help schools understand their existing challenges, resources, values and data related to inclusion. Tools like the Index for Inclusion Planning Framework and UNESCO school review framework can guide this process.

• They involve mapping resources, analysing data practices, forming implementation teams and setting priorities for inclusion.

• They form the basis for developing an action plan or implementation strategy for inclusive education in the school. This plan should include clear goals, activities, responsibilities and timelines.

• School reviews should be an ongoing process, not a one-time event. They allow schools to monitor progress, evaluate the impact of changes and make further improvements over time. This matches EEF guidance on effective implementation of change.

• They involve input from a range of stakeholders, including teachers, school leaders, parents, students and community members. This helps ensure the review and subsequent action plan is comprehensive and workable.

• Initial reviews often focus more on access and participation of students with disabilities or other disadvantaged groups. But over time they should evaluate education quality, learning outcomes and the experiences of all students to truly measure inclusion and accessibility. I have embedded a video from David Bara from WeCanAccess who exemplifies this drive for improving accessibility.

So in summary, school reviews are an important first step to understand where a school currently stands in terms of inclusion, what areas need to be prioritized for change and how to develop an action plan for transforming teaching, learning and the school culture to be more inclusive. They set the stage for successfully implementing inclusive education practices within the school.

Ensuring Your Model of Inclusion Is Neurodiversity Affirming

Neurodiversity-Affirming Language and Approaches for teachers

Embracing neurodiversity and employing neurodiversity-affirming language and approaches in education is essential for creating inclusive learning environments that celebrate and support the unique strengths and needs of all students. I also believe that, to improve retention and recruitment of school staff, that we need to make sure not just the education system, but the school itself are inclusive places to work. This section will explore the key aspects of neurodiversity-affirming language and approaches, including understanding neurodiversity, using person-first and identity-first language, avoiding ableist language and stereotypes, and tailoring teaching methods to individual needs. I have based it on the Beginners Guide To Ableism by Emily Lees. It is free to download from the tapestry website and was the subject of a discussion I had with the author.

Understanding Neurodiversity

Neurodiversity is the concept that human brains and minds are varied and diverse, with differences in neurological functioning being natural and valuable aspects of human experience (Armstrong, 2011). Neurodiverse individuals, such as those with autism, ADHD, dyslexia, or other neurodevelopmental differences, possess unique strengths and challenges that should be acknowledged, valued, and supported in educational settings (Armstrong, 2011; Silberman, 2015).

Using Identity-First Language

Language plays a crucial role in shaping our perceptions and attitudes towards neurodivergent individuals. Person-first language (e.g., “child with autism”) emphasises the person before the condition, while identity-first language (e.g., “autistic child”) acknowledges that the condition is an intrinsic part of the individual’s identity (Kenny et al., 2016). Many neurodivergent adults have expressed a preference for identity-first language, as it validates and celebrates their neurodiversity (Brown, 2011). teachers should be sensitive to the preferences of students and their families when using language to describe neurodivergent individuals.

Avoiding Ableist Language and Stereotypes

Ableist language perpetuates negative stereotypes and assumptions about neurodivergent individuals, reinforcing societal biases and marginalisation (Campbell, 2009). Examples of ableist language include terms like “high-functioning” or “low-functioning,” which can be limiting and stigmatising. teachers should be mindful of the language they use and strive to adopt respectful, empowering, and strengths-based language that acknowledges the abilities and potential of all students (Campbell, 2009).

Tailoring Teaching Methods to Individual Needs

Adopting a strengths-based approach to teaching involves recognising and valuing the unique strengths, interests, and developmental pathways of neurodivergent students. By tailoring teaching methods and providing appropriate adaptations and supports, teachers can create an inclusive learning environment that empowers all students to thrive (Kapp et al., 2013).

Examples:

Eye Contact: Instead of viewing lack of eye contact as a weakness to be corrected, consider alternative ways a student may be demonstrating their attention, such as turning their body towards you or altering their body movements when spoken to (Kapp et al., 2013).

Play: For students who may not engage in traditional modes of play, it is important to explore and value their preferred activities and special interests, recognising the unique developmental pathways they may be following. I believe that play is essential for all children and there are many different ways to play we need to value.

What is Inclusive Practice?

Implementing Inclusive Education in the Classroom

This section will discuss five key components of inclusive education: Universal Design for Learning (UDL), differentiated instruction, assistive technology and accommodations, peer support and cooperative learning, and social and emotional learning (SEL).

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework that aims to create flexible and accessible learning environments that accommodate the diverse needs of all students (Rose & Meyer, 2006). UDL is based on three principles: multiple means of representation, multiple means of action and expression, and multiple means of engagement (CAST, 2018). By incorporating these principles, teachers can design lessons and activities that cater to different learning styles and abilities, thus promoting inclusion and reducing barriers to learning (Rose & Meyer, 2006).

Differentiated Instruction

Differentiated instruction is a teaching approach that involves adjusting content, process, and product to meet the unique learning needs and preferences of individual students (Tomlinson, 2001). By providing multiple entry points and pathways for learning, differentiated instruction enables all students to access the curriculum, engage with learning materials, and demonstrate their understanding in various ways (Watts-Taffe et al., 2012). Differentiated instruction can be implemented through various strategies, such as tiered assignments, flexible grouping, and choice boards, to ensure that all students are challenged and supported appropriately (Tomlinson, 2001). The term differentiation is being slowly replaced in the UK by the term adaptive teaching.

Assistive Technology and Accommodations

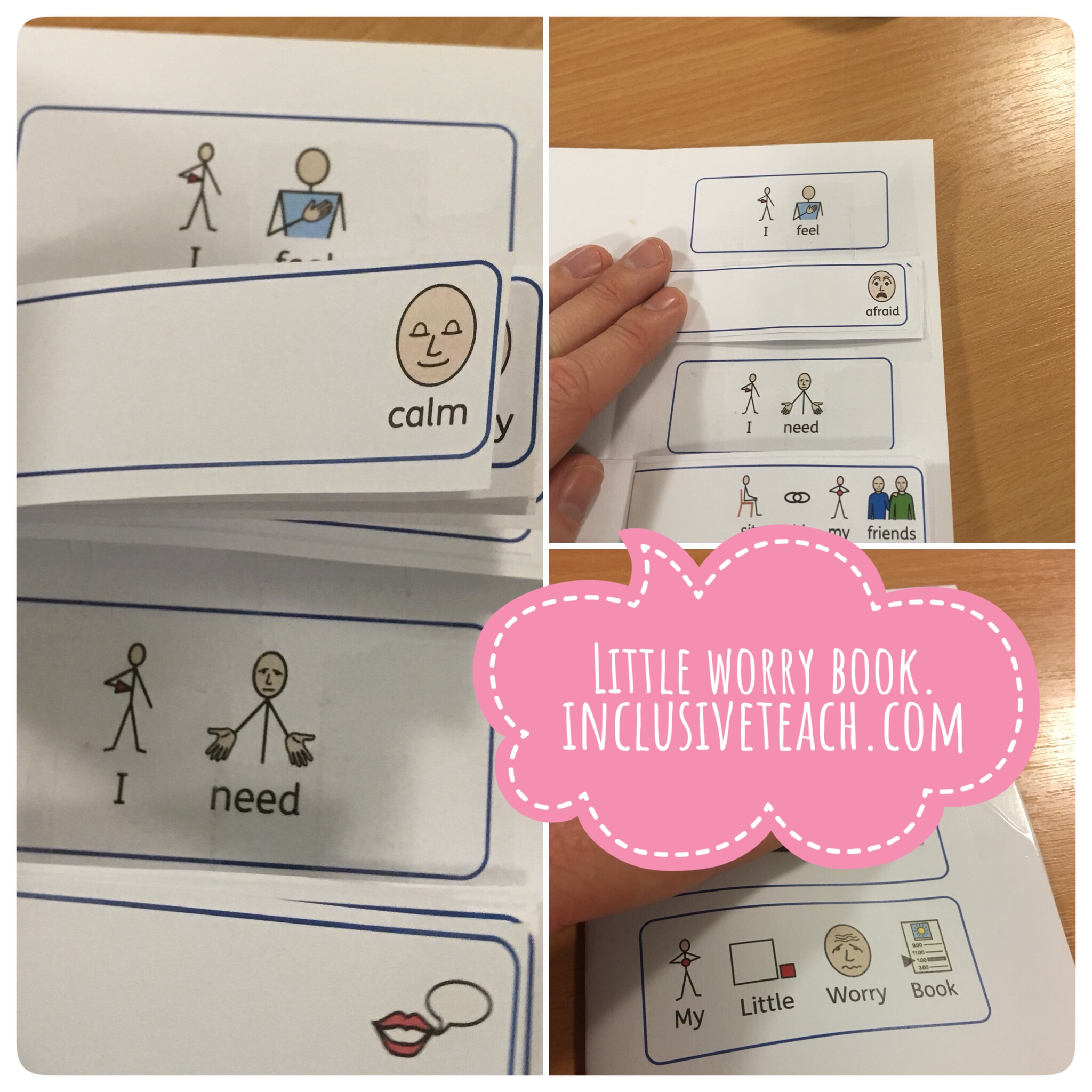

Assistive technology (AT and AAC) and accommodations are tools and strategies that support students with disabilities in accessing the curriculum and participating in classroom activities (Edyburn, 2010). Examples of AT include text-to-speech software, word prediction programs, and adapted keyboards, while accommodations may involve extended time for assessments, modified instructions, or preferential seating (Edyburn, 2010). Reading pens and even headphones that play white noise can help but require both investment an skilled teachers to use correctly.

Peer Support and Cooperative Learning

Peer support and cooperative learning are instructional approaches that involve students working together in small groups to achieve common learning goals (Johnson & Johnson, 2009). These approaches foster a sense of belonging, promote positive interdependence, and encourage students to support and learn from one another (Slavin, 2014). Research has shown that peer support and cooperative learning can enhance academic achievement, social skills, and self-esteem for students with and without disabilities (Johnson & Johnson, 2009; Slavin, 2014).

Social and Emotional Learning (SEL)

Social and emotional learning (SEL) involves the development of self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making (CASEL, 2021). Implementing SEL in the classroom can promote a positive and inclusive learning environment by fostering empathy, respect, and collaboration among students (Durlak et al., 2011). SEL can be integrated into daily instruction and classroom routines through explicit teaching of social and emotional skills, modeling and reinforcing positive behaviors, and providing opportunities for students to practice and apply these skills in various contexts (CASEL, 2021).

Challenges and Barriers to Inclusive Education

Inclusive education aims to provide equal opportunities for all students, regardless of their abilities or background, to participate, learn, and succeed in the classroom. However, implementing inclusive education can be challenging due to various barriers and obstacles. This article will discuss four key challenges to inclusive education: societal attitudes and biases, insufficient resources and support, teacher training and professional development, and overcoming obstacles through advocacy and collaboration.

Societal Attitudes and Biases

Societal attitudes and biases can significantly impact the successful implementation of inclusive education. Stereotyping, discrimination, and negative attitudes towards people with disabilities or from diverse backgrounds can create barriers to their participation and inclusion in educational settings (Forlin, 2010). In order to promote inclusive education, it is essential to challenge and change these attitudes and biases through awareness-raising initiatives, anti-discrimination policies, and the promotion of positive role models (Florian, 2014).

Insufficient Resources and Support

A lack of resources and support can hinder the implementation of inclusive education. This may include inadequate funding, limited access to assistive technologies, insufficient support staff, and a lack of appropriate learning materials (Hehir et al., 2016). To address these challenges, it is crucial to allocate sufficient resources and support to facilitate the successful implementation of inclusive education, including the provision of appropriate infrastructure, equipment, and personnel (Waitoller & Artiles, 2013).

The connections teachers make with their pupils and the adaptations the school makes to the environment has a huge impact. Often school buildings are full with news articles such as this one about children being taught in cupboards highlight some of the barriers schools face. I have found that children need space, when stressed a place to go that is quiet can help. The more pupils in one room the more chances of overstimulation.

Teacher Training and Professional Development

The successful implementation of inclusive education depends on the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of teachers. However, many teachers and even SENCOs may not have received adequate training in inclusive education strategies and practices (Sharma et al., 2009). To address this challenge, it is essential to provide pre-service and in-service training and professional development opportunities that focus on inclusive education, including pedagogical approaches, assessment strategies, and collaboration with other professionals (Cochran, 1998).

Overcoming Obstacles through Advocacy and Collaboration

Advocacy and collaboration are critical for overcoming challenges and barriers to inclusive education. This involves engaging with stakeholders, such as parents, teachers, policymakers, and community organisations, to raise awareness about the importance of inclusive education and to advocate for the necessary resources, support, and policy changes (Ainscow et al., 2006).

Collaboration between various stakeholders can lead to the development of innovative solutions and the sharing of best practices, ultimately promoting the implementation of inclusive education at the local, national, and international levels (Mitchell, 2014).

Conclusion: The State of Inclusive Education in The UK

While progress has been made in promoting inclusive education in the UK, there is still much work to be done. Continued efforts are needed to address the challenges and barriers to inclusive education, including changing societal attitudes and biases, allocating sufficient resources and support, and enhancing teacher training and professional development. These challenges have come to a head following the pandemic. Teacher retention and recruitment is low, teaching assistants who are essential for supporting pupils with additional needs are getting harder to recruit due to low pay and increasing demands of specialist skills.

By working together, teachers, policymakers, and stakeholders can ensure that inclusive education becomes a reality for all students in the UK, contributing to a more equitable and inclusive society that values and respects diversity. But it requires leaders both within the system and supporting education through initiatives such as #FliptheNarritive, autistic academics and advocates, amplification of the voices of people with lived experience. More than this we needs advocates who “get it” in the DfE and government as well as passionate individuals in local councils to ensure investment in the best possible education, not the cheapest.

References on Inclusive Education

Ainscow, M. (2016). Diversity and equity: A global education challenge. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 51(2), 143-155. Free

Ainscow, M., Booth, T., & Dyson, A. (2006). Improving schools, developing inclusion. Routledge.

Armstrong, T. (2011). The power of neurodiversity: Unleashing the advantages of your differently wired brain. Da Capo Lifelong Books.

Black-Hawkins, K. (2010). The framework for participation: A research tool for exploring the inclusive classroom. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(5), 427-440.

Brown, L. (2011). The significance of semantics: Person-first language: Why it matters. Autistic Self Advocacy Network. Now renamed and Retrieved from https://autisticadvocacy.org/about-asan/identity-first-language/

Campbell, F. A. K. (2009). Contours of ableism: The production of disability and abledness. Palgrave Macmillan.

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2021). What is SEL? Retrieved from https://casel.org/what-is-sel/

Cochran, H. K. (1998). Differences in teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education as measured by the scale of teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive classrooms (STATIC). Annual Meeting of the Mid-South Educational Research Association. New Orleans, LA. Free

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405-432.

Edyburn, D. L. (2010). Would you recognize Universal Design for Learning if you saw it? Ten propositions for new directions for the second decade of UDL. Learning Disability Quarterly, 33(1), 33-41.

Ekins, A. (2015). Implementing inclusive education: Issues in bridging the policy-practice gap. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(8), 861-875.

Ekins, A., & Grimes, P. (2009). Developing an effective whole-school approach. Continuum.

Florian, L. (2014). What counts as evidence of inclusive education? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 29(3), 286-294. Free

Florian, L., & Rouse, M. (2009). The inclusive practice project in Scotland: Teacher education for inclusive education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(4), 594-601. Free Report

Forlin, C. (2010). Developing and implementing quality inclusive education in Hong Kong: Implications for teacher education. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 10(s1), 177-184.

Hart, S., Dixon, A., Drummond, M.J., & McIntyre, D. (2004). Learning without limits. McGraw-Hill Education.

Hehir, T., Grindal, T., Freeman, B., Lamoreau, R., Borquaye, Y., & Burke, S. (2016). A summary of the evidence on inclusive education. Abt Associates. Free

Humphrey, N. (2013). Social and emotional learning: A critical appraisal. SAGE.

Humphrey, N., & Wigelsworth, M. (2016). Making the case for universal school-based mental health screening. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties,21(1), 22-42.

Katz, J. (2013). The three-block model of universal design for learning (UDL): Engaging students in inclusive education. Canadian Journal of Education, 36(1), 153-194.

Loreman, T., Deppeler, J., & Harvey, D. (2011). Inclusive education: Supporting diversity in the classroom. Routledge.

McLeskey, J., Waldron, N. L., Spooner, F., & Algozzine, B. (2014). Handbook of effective inclusive schools: Research and practice. Routledge.

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing.

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2011). About UDL. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl

Odom, S. L. (2000). Preschool inclusion: What we know and where we go from here. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 20(1), 20-27.

Oliver, M. (1996). Understanding disability: From theory to practice. Macmillan International Higher Education.

Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Salend, S. J. (2016). Creating inclusive classrooms: Effective, differentiated and reflective practices. Pearson. Now seems to be over £130 but I had an old copy.

Slee, R. (2011). The irregular school: Exclusion, schooling, and inclusive education. Routledge.

Thomas, G., & Loxley, A. (2007). Deconstructing special education and constructing inclusion. McGraw-Hill Education.

UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.PDF

UNESCO. (2009). Policy Guidelines on Inclusion in Education. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001778/177849e.pdf

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

Villa, R. A., & Thousand, J. S. (2017). Leading an inclusive school: Access and success for all students. ASCD.

Waitoller, F. R., & Artiles, A. J. (2013). A decade of professional development research for inclusive education: A critical review and notes for a research program. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 319-356.

Waitoller, F. R., & Thorius, K. A. K. (2016). Cross-pollinating culturally sustaining pedagogy and Universal Design for Learning: Toward an inclusive pedagogy that accounts for dis/ability. Harvard Educational Review, 86(3), 366-389.

Wigelsworth, M., Humphrey, N., Lendrum, A., & Neal, A. (2012). A review of key issues in the measurement of children’s social and emotional skills. Educational Psychology in Practice, 28(3), 255-272.

World Health Organization. (2011). World report on disability. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-VIP-11.01

7 Comments