Unlock the Potential of Play: Maximising Joy, Learning Outcomes & Play Types

What is Play?

While there are various definitions of play, there is no consensus on its characteristics. Some commonly cited characteristics include enjoyment, focus on process over product, and freedom from external rules. However, even heavily theorized definitions can draw on completely different characteristics. The elusiveness of play’s definition has been attributed to its ambiguity and the paradoxes it generates. Recent attempts to define play have settled on a spectrum of “playfulness,” which may further complicate the measurement of play to examine its correlates (Colliver et al 2022).

How Do We Determine What is Play?

So if adults don’t know what play is, do the children? Goodhall & Atkinson (2019) found that young children value having a say in the activities they engage in, which contributes to their perception of an activity as play. When children have the freedom to create their own rules or structure an activity, they are more likely to see it as play, even if it is typically seen as non-play. When adults provide too much structure or direction, children may not view the activity as play (Glenn, Knight, Holt, & Spence, 2012). This idea aligns with modern definitions of play, which view play as a continuum ranging from highly structured to unstructured, with unstructured play being the most play-like ( Zosh et al., 2018).

Here are four criteria that emerge from various definitions to determine if an activity is considered play:

- It should have no specific purpose or connection to survival.

- It often involves exaggeration, meaning it doesn’t necessarily follow the rules of regular, everyday life.

- It requires joyful and voluntary participation.

- It should be led by children rather than directed by adults.

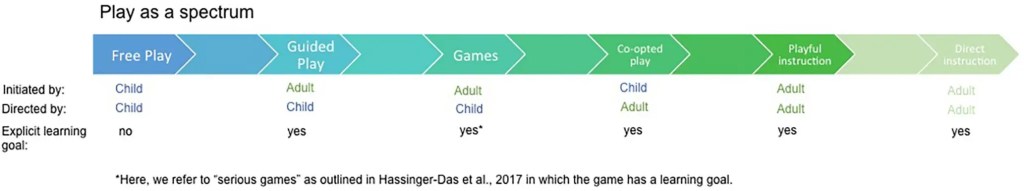

Play as a Spectrum

Zosh’s Theory that play is a spectrum is presented below, the most telling thing is that only free play has no specific learning goal. In special schools, EYFS settings etc I think there might be room for a category between Free and Guided play called “Facilitated Play”. Otherwise there can be no intentional learning. Further down this post we look at specific Play-Types that can be used to inform lesson planning.

Learning Through Play

When it comes to how young children learn, the idea is that they’re not just sitting around soaking up information like a sponge. They’re active participants who are building their own understanding of the world. This perspective is known as early cognitive development the most famous proponent and one of the few I remember from my PGCE is Piaget from 1962.

Play involves active and engaged thinking. When this kind of thinking is paired with guidance toward a learning objective in a playful environment, such as in guided play, children are more likely to be fully engaged with the information they’re learning. As a result, they’re more likely to retain that information compared to when it’s presented in a more passive way.

It seems to be accepted by the majority of teachers that active, discovery-based learning could be an effective way to teach (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2009). I would say this is definately true for EYFS specialists. Alfieri et al. (2011) reviewed 164 studies and found that when grown-ups supported children in discovering things (like in guided play), it led to the best learning outcomes. This was true for all kinds of things, like maths, science, computer skills, physical/motor skills, and even social and verbal skills – read more about this in our recent post and communication and AAC. Researchers have been studying this pedagogical approach, and they keep finding that the best way to learn is when adults help set up a fun environment where kids can explore and discover things on their own (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015).

To effectively learn, individuals must engage in a process of hypothesis generation, testing, and analysis of the results of their findings to inform their understanding. This method of knowledge construction aligns with Piaget’s theories. Learning is not a one-time event but rather an ongoing iterative process where individuals use their existing knowledge to generate new hypotheses, actively test those hypotheses, and update their understanding based on their results. Research into infant cognition, specifically their understanding of physical objects and relationships, has shown that even very young infants have expectations about the world around them, but these expectations become more accurate and nuanced with additional experience and development.

Play is Experimentation.

Guided play is like a controlled form of experimentation where children can try out different ideas within a set area of exploration. Playful environments encourage exploration and discovery, unlike traditional direct instruction settings that hinder active exploration. For instance, a study showed that children were more interested in playing with a toy when its cause-and-effect mechanism was unclear, compared to when it was already demonstrated to them (Schulz and Bonawitz, 2007).

Joy and Intrinsic Motivation

My other website is “The School of Joy Approach“. When researching this article the inclusion of Joy as a factor influencing the effectiveness of learning through play got my attention.

Joy is integral to play, scientific literature cites “positive affect” and “intrinsic motivation” as defining features of playful activities (Krasnor and Pepler, 1980). Joy is a central characteristic of play, even in the most restrictive definitions.

Positive affect has long been known to impact cognition. Ashby et al. (1999) proposed a neuropsychological theory linking positive affect to long-term and working memory, as well as creativity in problem solving. Positive affect is linked to increased creativity, which in turn leads to increased learning potential (Zosh et al., 2017).

The relationship between emotions and cognition is increasingly being understood. Fischer and Bidell (2006) describe the dynamic nature of development, where emotion and cognition are two sides of the same coin, and at the centre of the mind and activity. Research supports this notion, with psychology and neuroscience emphasising its benefits, including for learning (Seligman, 2002).

Beyond positive affect, surprise also impacts learning by increasing curiosity and exploration. In Stahl and Feigenson’s (2015) study, infants learned more when their expectations were violated, and were more likely to engage in information-seeking behavior and hypothesis-testing related to the observed violations. Neuroscientists are beginning to uncover the neural correlations between affect and surprise on learning (Betzel et al., 2017), possibly through increased dopamine levels, which are implicated in the brain’s reward system and motivation (e.g., Cools, 2011; Dang et al., 2012).

Intrinsic motivation is another essential element of play, as defined by Ryan and Deci (2000), and overlaps with our conceptualization of play.

16 Types of Play.

Bob Hughes, a play theorist, identified 16 different play types in his book “Playtypes: Speculations and Possibilities.”. The book is out of print but this document from Play Scotland is a fantastic resource. Not all of these are suitable for every child but would make a good reference point for planning “Learning Through Play” sessions. These include:

| Type of Play | Example | Learning Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Symbolic Play | Pretend play with dolls or action figures | Develops imaginative and creative skills, helps with problem-solving and social skills |

| Social Play | Playing games with friends or family | Develops social skills such as communication, cooperation, and negotiation |

| Socio-dramatic Play | Pretend play with roles and props, like playing house or school | Helps children understand different social roles and build empathy |

| Rough-and-tumble Play | Play fighting or wrestling with friends | Helps children develop physical skills, learn boundaries, and practice impulse control |

| Creative Play | Artistic activities like painting or drawing | Develops creativity and fine motor skills |

| Exploratory Play | Exploring and investigating materials or objects | Encourages curiosity, problem-solving, and scientific thinking |

| Mastery Play | Repeating an activity or skill to improve proficiency | Helps develop competence, confidence, and persistence |

| Object Play | Playing with toys or objects, like building blocks or puzzles | Develops fine motor skills, spatial awareness, and problem-solving |

| Language Play | Playful use of language, like rhymes or puns | Helps develop language skills, vocabulary, and communication |

| Storytelling Play | Creating or acting out stories with a group or alone | Develops imagination, creativity, and language skills |

| Fantasy Play | Pretend play with imaginary worlds or characters | Encourages imagination, creative thinking, and problem-solving |

| Constructive Play | Building or creating something, like with Legos or building blocks | Develops spatial awareness, problem-solving, and creativity |

| Locomotor Play | Play that involves movement, like running or jumping | Develops gross motor skills, coordination, and fitness |

| Recapitulative Play | Play that imitates adult roles, like playing store or doctor | Helps children understand different roles and build empathy |

| Game Play | Structured play with rules and objectives, like board games or sports | Develops social skills, strategic thinking, and problem-solving |

| Risky Play | Play that involves some level of risk, like climbing trees or riding bikes | Helps children develop risk assessment, problem-solving, and confidence |

5 Point Summary.

- Playful learning and guided play have characteristics that support optimal learning.

- Different types of play may be optimal for different types of learning.

- Guided play allows for efficient transmission of pedagogical knowledge while encouraging curiosity and exploratory play.

- Guided play helps children to focus on key learning outcomes and avoid distraction.

- Guided play allows for “constrained tinkering” that supports learning.

By acknowledging the different types of play on the spectrum, and the categories, we can gain a better understanding of why play, especially guided play, is linked to learning. This knowledge can help us create specific play-based teaching strategies that can enhance learning outcomes.

References:

Alfieri, L., Brooks, P. J., Aldrich, N. J., and Tenenbaum, H. R. (2011). Does discovery-based instruction enhance learning? J. Educ. Psychol. 103, 1–18. doi: 10.1037/a0021017

Betzel, R. F., Satterthwaite, T. D., Gold, J. I., and Bassett, D. S. (2017). Positive affect, surprise, and fatigue are correlates of network flexibility. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00425-z

Csikszentmihalyi, M., and Rathunde, K. (1993). “The measurement of flow in everyday life: toward a theory of emergent motivation,” in Developmental Perspectives on Motivation, ed. J. E. Jacobs (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press), 57–97.

Colliver, Y., Harrison, L. J., Brown, J. E., & Humburg, P. (2022). Free play predicts self-regulation years later: Longitudinal evidence from a large Australian sample of toddlers and preschoolers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 59, 148-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.11.011 Accessed Here April 9th 2023

Fischer, K. W., and Bidell, T. R. (2006). “Dynamic development of action and thought and emotion,” in Theoretical Models of Human Development. Handbook of Child Psychology, eds R. M. Lerner and W. Damon (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 313–399. doi: 10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0107

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Berk, L., and Singer, D. G. (2009). A Mandate for Playful Learning in Preschool: Presenting the Evidence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Zosh, J. M., Golinkoff, R., Gray, J., Robb, M., and Kaufman, J. (2015). Putting education in “educational” apps: lessons from the science of learning. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 16, 3–34. doi: 10.1177/1529100615569721

N. Goodhall, C. Atkinson How do children distinguish between ‘play’ and ‘work’? Conclusions from the literature Early Child Development and Care, 189 (10) (2019), pp. 1695-1708 https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1406484

Ryan, R., and Deci, E. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Schulz, L. E., and Bonawitz, E. B. (2007). Serious fun: preschoolers engage in more exploratory play when evidence is confounded. Dev. Psychol. 43, 1045–1050. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.1045

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic Happiness. New York, NY: Free Press.

Zosh, Jennifer M., et al. “Accessing the inaccessible: Redefining play as a spectrum.” Frontiers in psychology 9 (2018): 1124. Accessed Here April 9th 2023

2 Comments